I wrote about Dr. William Halsted’s life achievements, and about his vices, in the post https://witoldniesluchowski.com/how-did-a-cocaine-addict-change-surgery-in-america/.

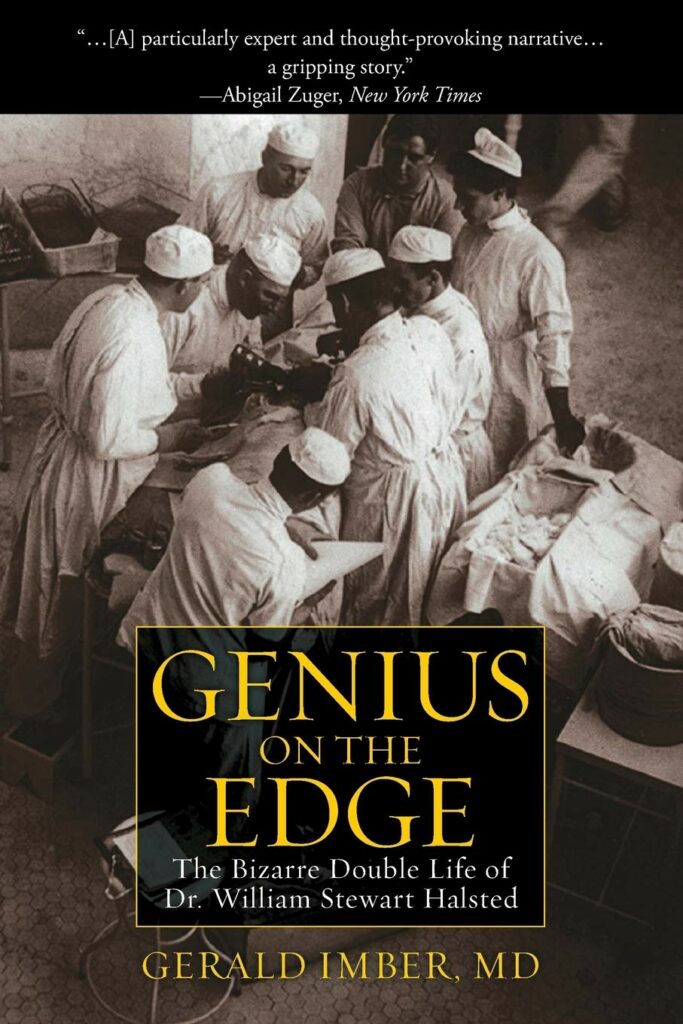

The book, Genius on the Edge, is, however, about a different aspect of his life story. It’s about how, out of nowhere, there appeared in Baltimore a medical excellence center. A world-class institution, and a hub for contemporary medical knowledge. The place delivering top medical care, and educating medical students in modern medical science. The story is about Johns Hopkins, and its founders, Drs. Welch, Osler, Kelly, and Halsted. The saga portrays the monumental life-time achievements of William Stewart Halsted.

Writing a book like Genius on the Edge is a monumental task. For the author, the first hurdle was to review the enormous number of the scientific literature, and the anecdotal facts. The more important, and more difficult, was the skillful selection from a multitude of facts and opinions. This process shaped the type of story which the author wanted to present to the world.

And Dr. Gerald Imber did a marvelous job.

Like unearthing Rome, the reader can discover many levels of the complicated life of Dr. Halsted. The most superficial, and sensational, is that of the prominent surgeon, throughout the most of his adult life, fought his cocaine and morphine habits. Halsted missed work, dropped from doing the surgery, just to be injected with a ‘fix’. They presented the story in a tabloid and catching version in the TV serial The Knick.

There is a short story of the love affair between the aging surgeon and young Elizabeth Randall. There is an uneasiness of Halsted seeing his friends from Johns Hopkins going to Europe to fight the Germans during WWI. Germany was a country where Halsted had many friends, the place where he learned surgery, and where he sent many of his residents to improve their medical education before starting many surgical subspecialties at Johns Hopkins.

There are stories about favoritism, gross overcharging for his medical services, abandoning his patients on the operating table and letting his residents finish the job. There are stories about leaving the hospital altogether, and isolating himself in the pastoral High Hampton, his estate in the North Carolina. Or departing to Europe without leaving a trace. There are reports about his intolerance to the slightest deviations from his instructions. The anecdotes about pedantry in the way he dressed, getting his shoes from England, shirts from Paris, and even having his shirts cleaned and pressed on the Continent.

But this was all a side-show, the distractions. All adding up to a deep humanity of the person. For the reader, the real story is about putting yourself in his position, his times, being aware of his health, and still being able to create his opus magnum.

It’s like watching Sidney Crosby scoring from the impossible angle the winning goal in the 2010 Olympics. Or Pavarotti singing 9 high Cs within just 2 minutes in ‘La fille du Régiment’. Or Michelangelo painting the ceiling while on his back.

How did they do it?

The actual story is about Halsted formulating and standardizing the training program for the generations of all modern surgeons in the United States. It’s about creating a health care excellence center, a model for the many to come. It’s about having the vision of where the science and practice of medicine is going, and creating many new surgical subspecialties. It’s about the meticulous surgery, attention to details, and deciding which details are important. It’s about the essence of surgery. About favoring principle over speed. And delivering the medical care his patients flocked to from around the country. It’s about creating the product for which the customers are happy to pay the exorbitant amount of money. And if you couldn’t afford, you didn’t pay.

All this fighting the ferocious beast of addictions.

He helped create the brand of Johns Hopkins. The brand, which was comparable to emerging oil companies, retailer stores, railroad and food giants. At that time, these brands kept sprouting all over the country. Johns Hopkins was right there with the best of them.

He trained surgeons, slowly, one at a time. Only 17 residents could claim they were his pupils. They, and their students, often after graduating, departed and opened their own training programs all over the country. In Cincinnati, it was called a Hopkins invasion, when three consecutive chairmen of surgery trained in Baltimore. Teach and release the final product.

And Dr. Gerald Imber painted a superb picture of a man who created the iconic entity. The picture of a man with the passion. Man who realized his vision without compromising the principles. And he achieved his goal despite the monstrous addiction.

Good job, Dr. Imber!