When a father helps his son, they both laugh. When a son helps his father, they both cry.

Yiddish proverb.

One of the most consequential decisions of my life was to bring my parents from Poland to the United States.

While they were getting older, I realized my parents’ future looked grim in Poland. Communism maintained a tight grip on the economy, politics and our social life. Martial law was imposed. The unrest crossed brewing point and spilled on the streets. For my parents, everyday survival got to be a challenge and, most importantly, their medical care was dangerously compromised. They didn’t complain, but I knew the reality. Their future looked grim.

Together with Bonnie, we’ve decided to offer them to move to the United States. At that stage of our lives, we were building a new house. It was big enough for two of us, and our four kids. Part of the house was built as a granny flat. Quite a neat separate living place. Bedroom, living room, kitchen, and a nice patio with an ocean view. Bigger and nicer than the place they had in Warsaw. And still attached to our house.

They agreed. We allowed them a year to close their ties with the old country and mentally get ready for the restructuring of their lives.

We thought one year was enough.

I took one week off my work to fly them and their belongings back to the United States.

I don’t know why, but I expected them to be packed, sitting on the suitcases, and waiting for me to bring them here. And having the money from the sale of their apartment.

When I walked to their living quarters, the place I’ve spent some twenty-five years of my life, I realized my blunder. Nothing was done. Moreover, it looked worse than the place I’ve left. I’ve recognized some pieces of furniture from my youth, but there were quite a few new ones. The place was packed. There was a narrow path to the bedroom, another to the kitchen, and, the narrowest, to the bathroom. The walls of the apartment were closing on them. I faced a potential disaster. When I asked them why nothing was done, my father had a blank stare, my mother was apologetic.

I understood that every table, chair, and every painting was dear to them and from the emotional, and practical point, it was easier to keep the item rather than to get rid of it. They probably knew that no one will pay them the value they’ve attached to their possessions. Another reason to keep them. Everything had emotional value.

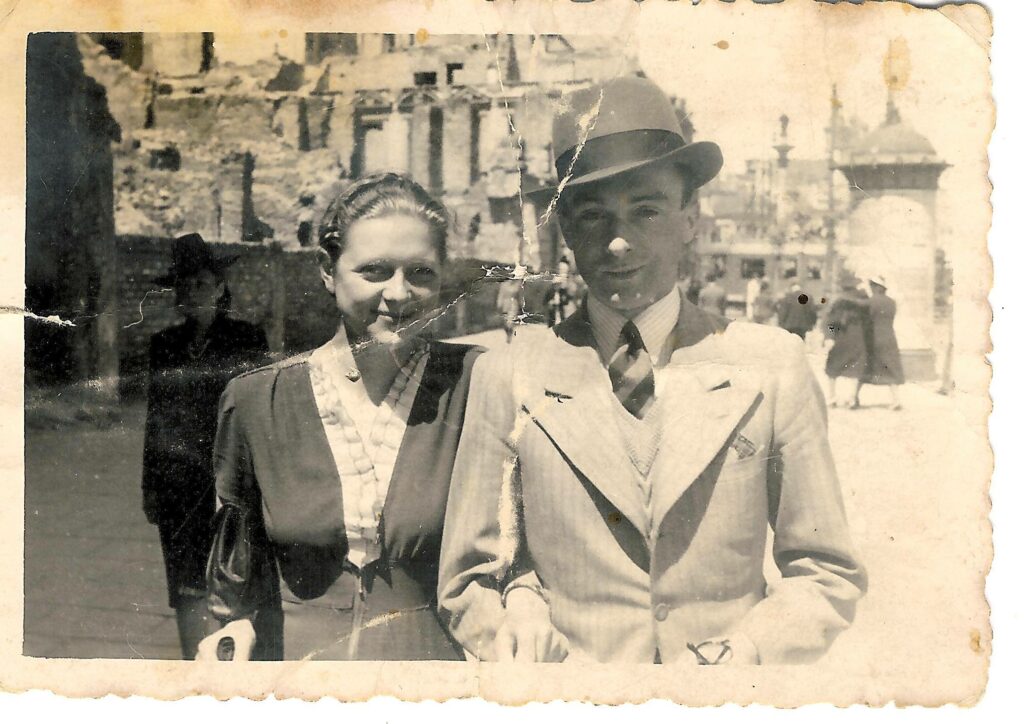

In the next few days, I’ve tried to sort out their lifelong belongings down to the manageable minimum. We sold or just gave away the furniture. I’ve packed most of the necessary items and shipped them to California. The neighbor let me use his dolly, and I became good friends with a lady in our post office. I took particular care in preserving dad’s book collection. Some items were at night disposed of in a local dump. However, I could preserve all the important heirlooms, certificates, and many pictures. Fortunately, my parents found a buyer for their prized possession, the apartment, but the money didn’t change hands yet.

Our flight was leaving Warsaw at 6 am. The night before, we finally had our suitcases packed, the apartment cleaned, sort of, and mother got the money from the buyer. We had a taxi booked for 2 am. At 10 pm, I walked to my neighbors’ place to stretch my legs before a long-awaited flight. Passing by the living room, I saw my father, sitting in the lonely chair in our living room. He was already dressed in his best suit, white shirt, and a tie. His brown felt hat was on the suitcase standing next to him. He had this look I didn’t like.

“Is something bothering you, dad?”

No answer.

“What’s wrong?”

No answer. He just shook his head.

“Can you tell me?”

He looked at me, held my stare for a couple of seconds.

“I’m not going.”

“What?”

“I’m not leaving.”

I looked at my watch. It was almost midnight and our plane was departing in 6 hours.

“Dad, we are packed, we have passports, tickets, and visas. The apartment is not ours anymore.”

“I’m not leaving this place.” He looked at me. “You don’t transplant the old trees.”

“Dad, we’re talking about it for the entire year.”

He did go. During two legs of our journey, he behaved like a ghost. The long coat put on in Warsaw, dad took off in Miami. Same with his hat.

Dad didn’t live much longer. In a month, he ended up in the ER in Miami with critically low hemoglobin. Bone marrow biopsy showed advanced leukemia. In the old country, he was treated for aplastic anemia. Dad died in his bed, in a foreign country, with my mom holding his hand.

Did he know his fate? Did he think he may not reach the promised land in California? Now I know his tree was too old to be transplanted.