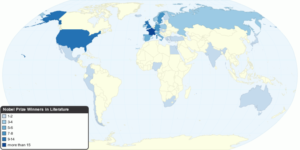

I shouldn’t complain about the Nobel Prize in literature. Polish writers received this prestigious award five times, and, by the numbers, we are in the top of so distinguished countries. Not bad.

But when you think about the idea of rewarding a person for being the best writer in the world, and about the convoluted process how the Academy selects the winner, your eyebrows go up and your skin cringes.

First, how do you choose from thousands and thousands of the literary works published on our planet every year? From plays, through the novels, poetry, up to the songwriting. How do you compare a novel written in Polish to the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore? Who makes a judgment? How do you measure the impact? Do the translators get a part of the award? I often read a story written in Polish, and then it’s translation into English. Sometimes the difference in the quality is clearly palpable.

Where in the world do you place the lyrics to the popular songs written by the singer, who, granted, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom? After the announcement of the award, Bob Dylan did not respond to the letter from the Nobel Prize committee and did not attend the ceremony. He had his medal and diploma handed during a dinner with all twelve members of the Academy, with no press and no public present, and an obligatory lecture he published on the internet.

Over the years, the Prize has become less literary and more political. The original idea, expressed vaguely in Nobel’s will, later was highjacked and modified according to the changing times and sociopolitical views of the Academia. By the nature of their writing, writers are often associated with social and political problems. But it’s fascinating to watch how often the needle goes to the left and how often to the right.

The list of the controversies in impressing. The Committee rejected Tolstoy, Zola, Ibsen, Twain, and Chekhov. It did the same with the eminent Indian writer Narayan. Sweden got 8 laureates, having the Academy members giving the awards themselves. The public lambasted many laureates for their political views. Many did not get the award because of the fear of stirring up the political conflicts. Jorge Luis Borges didn’t get it, deliberately, considering his ardent anti-communist stance. Consequently, the Academy recognized Jean-Paul Sartre and Pablo Neruda, staunch supporters of Stalin, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, a close friend of Castro. Most recently, the Academy balked on Salman Rushdie after the Ayatollah ordered to kill him.

There is always a question of how much the views, other than in the candidate’s expertise field, should affect the nomination process. We all have opinions, and often our personal lives are controversial. The writers are no exception, and I would argue that are affected more often than not. But they have the megaphones and access to the masses. I know for sure that totalitarian regimes widely use writers to propagate the official government positions. This kind of pressure was rampant in communist Poland. I also know that you didn’t have to press them hard to loud, our beloved leaders. Associated perks compensated for the moral questions if even there were any. They just had to play the official tunes. In the country of equals, they were more equal than others.

But the Academy must be consistent. To do it otherwise leads to the corruption of the award.

This year, the committee did not choose a winner. A sexual assault scandal rocked the Academy to the point, that the King had to intervene. One of the Academy members told the press that the body is in crisis and needs to be rebuilt.

The biggest scandal, however, has happened in the awarding of the Peace Prize. But this is a topic for one of the next posts.