The year was 1881 and a woman bled after childbirth. The family contacted a young, 29-year-old surgeon. After deliberations, he drew blood from his own vein and transfused it to the patient. The patient recovered. German scientist Karl Landsteiner, with the help of a Polish serologist Ludwik Hirszfelt, discovered and described the ABO blood group system 20 years later.

A year later, the young woman’s mother was having severe abdominal pains. Consultants didn’t know how to treat her, since they couldn’t make the diagnosis.

Again, the same surgeon was called. He diagnosed cholecystitis and promptly operated on the elderly woman. The patient recovered. The story goes he operated on the kitchen table at 2 a.m. using a light above the table. The first elective cholecystectomy was done by Carl Langenbuch in Germany the same year, a half of a world away, this time in the formal operating room.

The young surgeon was the first woman’s brother, and, of course, the son of the older woman.

In those times, doing surgery at the patient’s home was not unusual, especially for the private practice patients. Doing surgery on one’s own mother––was.

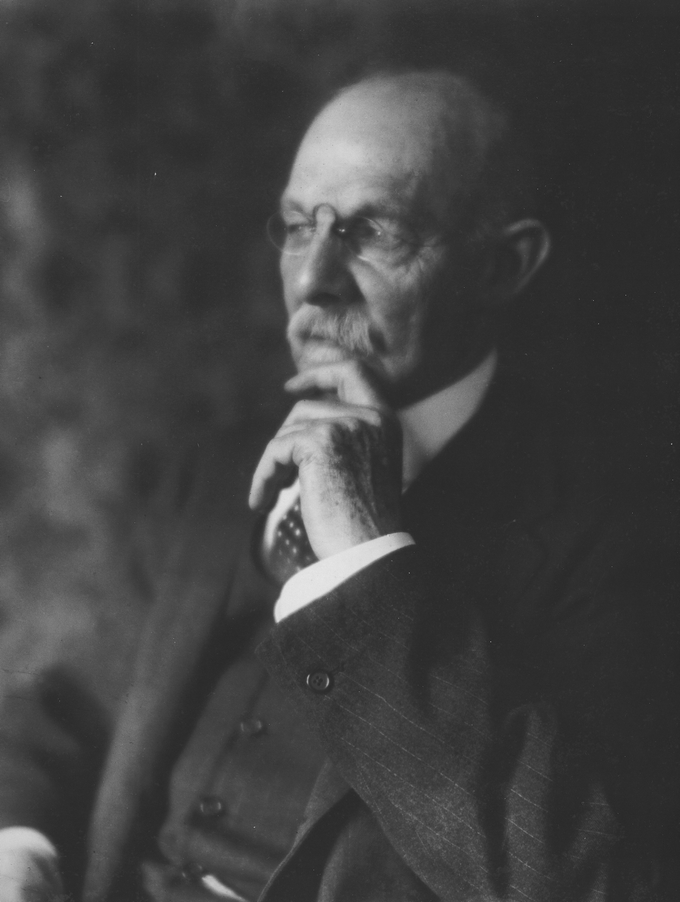

And it was just the beginning of a long and very eventful career of Dr. William Halsted.

Halsted went on to become a giant in the history of American surgery. He established the surgical program at Johns Hopkins as a model of the American surgical prowess, including precision of the diagnosis, meticulousness of surgical technique and unusual attention to details. He also established the training program for surgical residents based on the German system, which was modeled on apprenticeship training for the trades. There was no time limit for the length of surgical residency, and the trainee was ready only after his mentor had said he was. One of Halsted’s residents, after 10 years working with him, asked when he will be able to start his own practice.

“Why hurry?” was his answer. “There is no rush!”

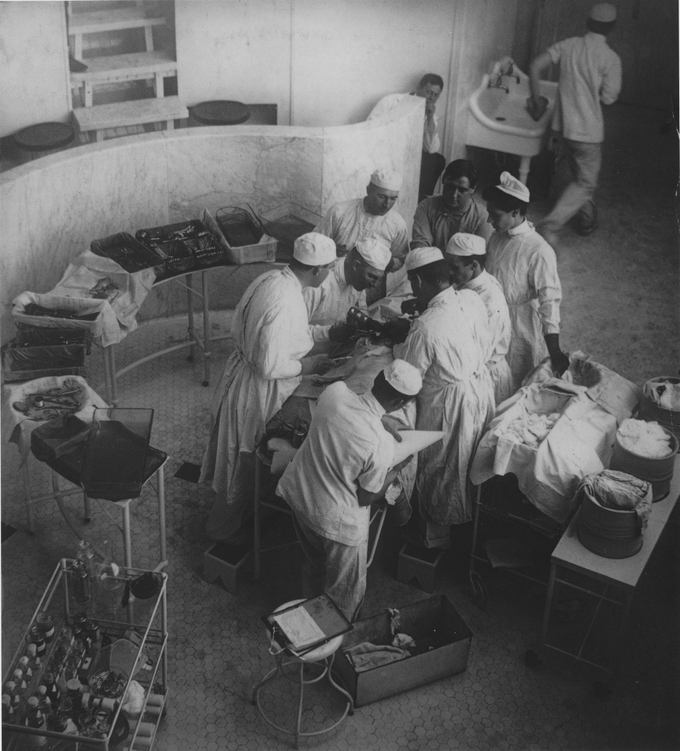

That’s a ‘Dream Team’. Dr Halsted, slightly hunched, operating. The anesthesiologist using the ether cone to deliver the mixture of gases. All wear surgical caps, there are no masks. The surgery takes place in an auditorium.

Those days the operations took longer, too. Before Halsted, the surgery had to be done swiftly, given the fact there was no anesthesia. The speed was everything. Amputations lasted minutes, removal of bladder stones took as long. The assistant had to be careful. Otherwise he could lose his fingers. Halsted operated with the rudimentary ether anesthesia, and could take his time doing meticulous surgery. And he did.

There is a story, which some say is apocryphal, that Will Mayo visited Johns Hopkins and was observing Dr. Halsted perform a radical mastectomy. It is said that the older Mayo brother stepped out of the operating room shaking his head after 2 hours and said: “My God, this is the first time I have seen the wound healing at the upper end while it is still being operated upon at the lower end.”

Halsted was the one who first used surgical gloves. But not for the reasons we use them today. At his time, the operating team dipped hands and forearms in carbol to disinfect them before the surgery. Unfortunately, the chemical was so strong, that it left skin burned and discolored. Halsted himself didn’t mind it, but his scrub nurse did. The fact that she was his girlfriend, and a future Mrs. Halsted, helped. So, he wrote a letter to the Goodyear Company and asked them to design rubber gloves. Soon the entire operating team was using them.

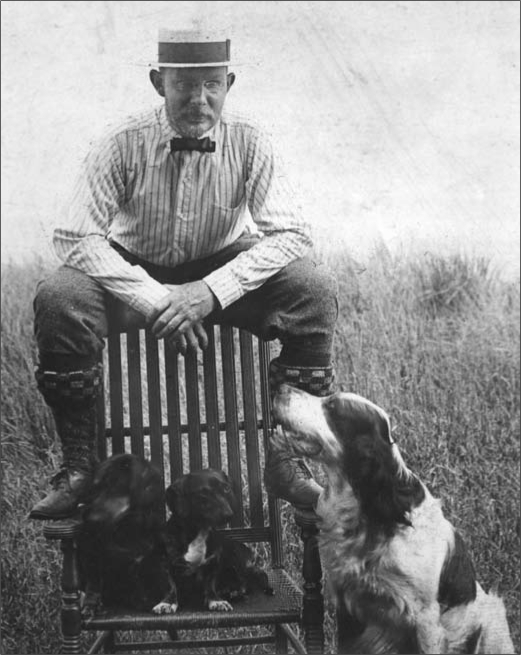

Halsted applied the floating scale for determining his fees. He often transported, hospitalized, and operated at Hopkins upon individuals from the North Carolina mountains around his summer home, High Hampton. With these “neighbors,” the Halsteds would cover all the expenses themselves. At the other end of the scale, one can find a bill submitted for amputation for a popliteal artery thrombosis for $13,825, and this, of course, was in the years before the income tax.

The search for perfection was obvious in many areas of Dr. Halsted’s daily life. He imported his shoes from a particular Paris boot maker. Other leather goods came from a specific London firm. For many years. There is the story about Parisian laundry slips. His linen shirts he mailed abroad, to Paris, for quite some time because he could not find a laundry in Baltimore that could launder a dress shirt to his satisfaction.

But Halsted also had a dark side to his life. He was a cocaine addict. Many times he had to interrupt surgery to be injected with cocaine by a nurse. Later on, he tried to cure his cocaine addiction with morphine. Halsted became addicted to both. It’s difficult to understand how in the world he maintained such a productive life for thirty-some years, having up to a three-gram-daily cocaine habit. Congress had passed the first legislature regulating cocaine in this country in 1914.

How to assess the enormous achievements of this man, considering the fact he was dependent on cocaine and morphine? In his time, cocaine was not illegal. It was imported after the initial craze in Europe. Sigmund Freud heralded the miraculous powder himself. I see Halsted as a giant climbing the pinnacle of surgery, despite the monstrous habit.

He himself fell the victim of complications of the disease he dealt with daily. In 1919, Halsted underwent cholecystectomy. The surgeon did not remove all the stones, and Halsted died in 1922 of complications, probably sepsis.

His wife died 3 months later.

Halsted never operated on the heart. His work, however, created the environment where Alfred Blalock in 1944 did his first “blue baby” operation. By that time Johns Hopkins became the powerhouse not only as a medical school, but also as a center of the medical and surgical knowledge.

But Alfred Blalock’s story is for the next blog in the cycle of Cardiac Surgeons.

From the entire reading I did for this blog, I want to cite just three sources: