My uncle died in Poland during the implant of his permanent pacemaker.

At that time, I was a medical student, and I thought I should be able to understand why did it happen. I couldn’t, and I still don’t.

A few years later, I came to this country and started doing the implants myself. It’s a simple surgery, but it’s only easy if the doctor knows what he’s doing.

The first part of the procedure, pocket creation, seems to be a basic surgical job, but I can’t even tell you how many infections I have treated in my life. The cardiologists did an original implant in many of them.

For the next step, insertion and proper positioning of the pacemaker leads, like with many procedures not done under direct vision, the surgeon must show skills. The complications there are immediate and could be catastrophic. The entire surgery shouldn’t take more than a half-an-hour, but I’ve seen some lasted whooping several hours. Someone joked that the radiation from the image intensifier burned a hole in the floor of the operative suite. The joke is cruel, considering the patient’s exposure to radiation.

But the procedure was not always as slick as it is now. Nor the device as wonderful.

In 1932, Hyman built the first pacemaker powered by the crank. Later, the idea of artificial pacing was, fortunately only for a time being, abandoned. The device was bringing the dead to life, and that skill was reserved only for the highest power. The list of the doctors, engineers, and the ordinary inventors, who contributed to the development of this little marvel, is long and still growing; while the size of the device is getting smaller and smaller.

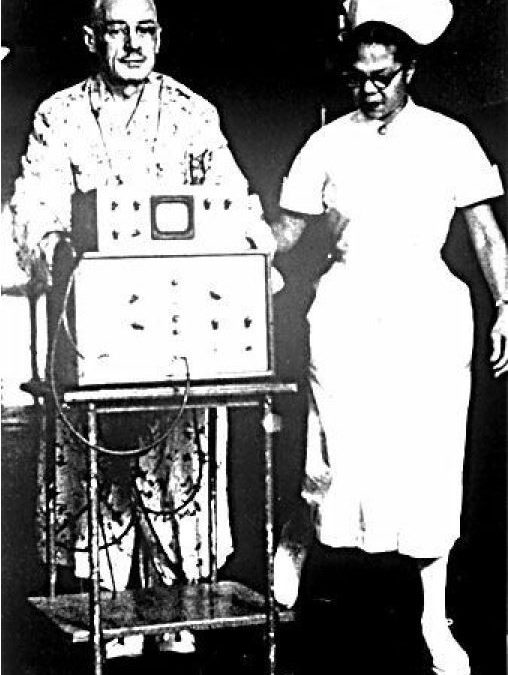

The first portable pacemaker was external. Located on a cart, had to be wheeled by the nurse. Or could serve as a walker.

In the 1970′ we were implanting Medtronic workhorse model, 5950.

The latest are the size of a silver dollar.

But wait! That’s not all. The newest pacemaker, freshly approved by the FDA, is the size of a pill. And it doesn’t even need the leads. The surgeon implants directly to the heart muscle with a catheter.

During my career as a surgeon, I’ve seen astounding progress in cardiac technology. I don’t remember the times when the public accused the scientists of usurping the powers of God. But I remember the first patient with an implantable device. The Swede burned through 26 different pacemakers, lived to be 86 and outlasted not only the inventor of his pacemaker but also the first surgeon who had implanted it. I also remember the first nuclear pacemaker, implanted in my Medical School in Warsaw. There were two problems with the idea. First, we rarely need such a long-lasting battery, the second was the logistical problem of what to do with the radioactive power source after it was not needed anymore. The lithium battery still is the best––until Tesla will come up with something better, and we know they need it.

There are pacemakers implanted into the patients, who, for one reason or another, don’t live long. The idea of re-using these expensive devices seems logical and is quite appealing, but the process of approval seems to last forever. And, in my opinion, will never end. I can see the long fingers of the manufacturers and their lawyers pushing Temida’s scale in their interest.

But, whatever the optics are, whatever the politics and the dark side of the money behind the development of these little cardiac helpers, the progress I’ve observed, is astounding. And it only took but a part of my life.

But, again, I’m privileged to live in such stunning times, and yet knowing the best is still to come.