Ostensibly, it was all about the first implantation of an artificial heart. Argentinian surgeon, Domingo Liotta, started to work on the project at the University of Córdoba. And he was not even the first one in the history of medicine. Liotta, after his initial studies were published, was asked by DeBakey to continue his work at the Methodist Hospital in Houston. After a few years of work, and watching the results of the implants on calves, DeBakey still didn’t think that the device was ready for prime time. The complications’ rate was high and animals were dying. So Dr. Liotta moved to the lab administered by Denton Cooley, and there he continued the work.

In 1969, Cooley thought he saw enough, and decided he was ready. He implanted the device into the chest of the terminally ill patient.

On that memorable day, DeBakey was out of town, and, when he found out, he strongly denounced Cooley, accusing his past associate of theft, immaturity, and unethical yearn to claim the medical “first”. DeBakey said the device was his, while Cooley maintained he was the one who worked on that particular model with Dr. Liotta.

Instantly, a fault running between The Methodist Hospital and Texas Heart Institute, two world-famous health care centers, which are located essentially on the same campus and separated only by a few minutes walk, a fault created when Cooley a few years before separated his practice from his mentor’s, had ripped, and sent seismic waves throughout the medical worlds, and cardiac surgical centers in particular. After the initial cosmic earthquake, the following aftershocks continued for years. Then the Cold War ensued, and it took forty-some years to bring these two giants together in a very public attempt of reconciliation.

The feuds are nothing new. They constantly happen, between all kinds of people, in all professions, in all social circles, in all walks of life. Salk and Sabin, Harken and Bailey, Gallo, and Montagnier, Hatfields and McCoys. Let’s add Duke and UNC. I remember close rivalries on every level of my personal and professional development. I had more or less visible rivalries in my elementary school, high school, and music school. I had friendly rivals during my medical training and on the volleyball court. Then even during my career as a surgeon. Some more involving than others. Some friendly, the others not so. One in particular was quite damaging. But most of the time, they’ve brought out the best in me, and most of the time, neither I nor the people around me were hurt.

But we have to separate rivalries from feuds, and then from open wars. They all ensue between the neighbors, close associates, often friends, spouses. And then between the countries. My native Poland had a slew of those throughout our history.

Houston rift, in retrospect, was quite predictable.

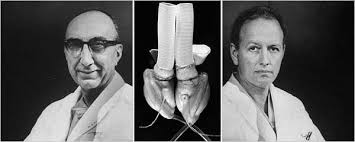

DeBakey was a ‘brainiac’. Exceptionally smart, skilled organizer, gifted politically, tireless worker, intolerant of mistakes, be it his or the people working with him. He had a well-balanced, matured view from above. Good surgeon, but also knew when to stop. An excellent strategist.

Cooley was more a ‘doer’. Having perfected the surgical technique, he prided himself on the fastest, most expeditious way of doing surgery. His block of operating rooms was like Ford’s assembly line, with Cooley walking from one to another, like grandmaster playing simul with a collection of the other chess players. Cooley proudly announced the first heart implant took him “just 47 minutes.” After Christian Barnard, to the world’s surprise, did his first heart transplant at Groote Schuur in Cape Town, gracious Cooley sent him a note: “Congratulations, Christian, on your achievement. I’ll be reporting on my first one hundred soon.”

Ideally, these two types of skills should complement each other to form an ideal profile of a surgeon. In Houston, however, those two clashed.

The time for reconciliation came in 2007. Cooley was 87, and realized their time was running out. DeBakey 98, just recovered from the extensive and dramatic surgery. After the older man came home, Cooley stopped at his house. His wife opened the door and Cooley asked if he can see her husband. She said Dr. DeBakey was not having a good day and refused the visit.

“As time passes, I have a growing desire to meet with you and express my gratitude for the influence you have had on my life and career,” Cooley wrote. “Especially, I am grateful for the opportunity you provided me more than 50 years ago to become established at Baylor and to be inspired by your work ethic and ambition. Those years remain in my memory.”

The wide celebrated truce came during the meeting, when DeBakey got awarded an honorary membership of Cooley’s surgical society. DeBakey promised he will reciprocate with one of his own.

Now, after some fifty years, it’s a good time to take a second look at the work of these two giants.

Cooley’s both pioneering procedures raised objections. His human heart transplant and the artificial heart implant created legal and ethical problems. He knew, or should have known, he was working outside accepted canons of surgical science.

The objections raised by DeBakey were sound. The heart transplant was relatively easy to do technically. But the patients initially die of rejection, and/or infection. Cooley himself had to suspend the heart transplant program in his Texas Heart Institute. This had changed with the advent of cyclosporine. Complications of the artificial heart implant were a little different. Blood clots were devastating, and continuous use of blood thinners exposed the patients to bleeding. Even now, the original dream of replacing the human heart permanently with a man-made device is still unreachable.

The indications have changed, and now the mechanical device is generally used only as a temporal bridge to human heart transplantation. There is still no mechanical device that can fully replace the real thing. The human heart remains stubbornly resistant to total replacement, its physical mysteries nearly as challenging as the metaphorical ones that have plagued us since the beginning of time.

For all the progress in medical knowledge, the human heart, mechanically just a simple pump, defies even crude imitation.