In 1953, March 6th happened on Friday.

When I came to the class in the morning, I saw my third-grade teacher sitting at her desk, head buried in her hands, crying. We sensed a personal tragedy, and not knowing how to react, quietly took our seats.

She then looked at us with the teary eyes.

“Our father had died. How are we going to live now when he’s gone?”

Then we understood why our only radio station for the last couple of days played exclusively solemn classical music. Mostly Chopin and mostly funeral marches. The official news just today announced the reason, and we found out what caused Mrs. Konopkowa to cry.

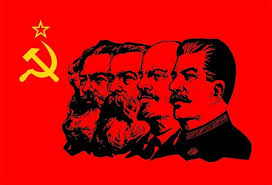

Stalin had died a few days ago.

The thick cloud covered the Earth. At least the East part of it. The USSR Central Committee displayed his body in state at the House of Columns. The visitors came here to view their leader. Many cried, some died, crumpled and crushed by the amassed crowds.

The Polish communist officials initially took a defensive approach, putting the security forces on alert. They all waited for the official reaction from Moscow. The ordinary Poles were hopeful for a peaceful and meaningful change and did not resolve to violence.

In a few months, it became clear that nothing had substantially changed.

Later on, from our parents, and from the clandestine sources, we found out the real dimensions of Stalin’s depravity. Political murders of his opponents, staged trials and execution of his closest collaborators, liquidation of the top military commanders right before the German invasion, forced collectivization of peasants with the subsequent wide-spread famine in the countryside, mass executions during the Great Terror, pandemic deportations of the innocent civilians, the enemies of State, to Siberia. That’s not even to mention the crimes done in Poland.

I remember the forceful russification of my generation. The control of the radio, press, and the corruption of writers was the first step. The government not only encouraged but prized denunciations. The common response to any political joke was, ‘Do you know who built the Volga-Don canal?’ The Volga-Don canal was a massive Russian project connecting the waterways of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The Soviets had an abundance of political prisoners to use them as a workforce. One day on the project counted as three days in prison. This was not a joke.

My father told me a story about the communists’ insistence on helping the young mothers to concentrate on work without the worry of carrying for their children. The Soviet state created famous week-long kindergartens, where working mothers dropped their children on Monday and picked them up on Saturday. One Saturday, a mother came to take his son home and realized that the boy, given to her by a teacher, was not hers.

“That’s not my child,” the distraught woman said to the caretaker.

“It doesn’t matter. You’ll bring him back on Monday anyway,” she heard the answer.

They’ve learned from Aristotle: “Give me a child until he’s seven, and I’ll show you a man.”

There was no private property, everything belonged to the state and no one cared for the common goods. Most of the people worked for the government. My father, a high-positioned corporate lawyer, received the salary of a skilled worker. “They pretend to pay us, so we pretend we’re working,” you’ve heard on the streets. If you were not a member of the Communist party, your future was uncertain. When a father disciplined his son, the vengeful boy could go to the police and tell them the father listens to Radio Free Europe. The head of the family ended up at the least interrogated, and often sent into exile.

My elementary school teacher, Mrs. Konopkowa, bless her heart, was as good a teacher as they come. But she was also indoctrinated by the state and did her best to impose the official values on us. We had a Swedish boy in my class, whose father was a member of the embassy staff. One day, he brought to class a box of chocolates in the shape of a cigarette case. In the fifties, an item as such was a rarity in Poland, and our eyes popped open. He gave it to our teacher, who initially gracefully accepted the gift. But then she walked back from her desk and returned the case.

“I cannot accept the gift from the capitalist country,” we’ve heard her answer.

I still remember the name of the boy––Bjork Borg.

Just another example of the criminal level of knowledge disseminated in the school system.

The democracy without the proper education ends up in a disaster.